By Justine Trinh

“Let me begin again.”

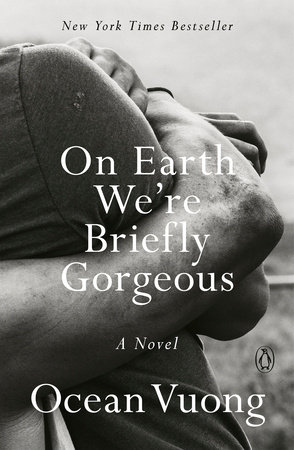

Poet Ocean Vuong starts off his first novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, with these words. They are the same four words I kept telling myself as I struggled to re-read this book. The first time I picked it up from the library, I devoured it in one sitting. But this time around, I had to start over multiple times, leaving it around the house for my future self to stumble upon and resignedly say, “Let me begin again.”

Why was it so difficult to re-read this book? It’s not Vuong’s poetic prose, which is beyond gorgeous; each sentence saturated with nuance that haunted me for hours after the initial reading. Rather, it was the subject matter because it was personal to me as a child of Vietnamese refugees. Vuong perfectly encapsulates the hard, conflicting feelings of growing up with parent(s) traumatized by the Vietnam War.

Within the Vietnamese American community, there is a desire to move away from the Vietnam War. After all, the war ended forty-seven years ago, and contrary to popular belief, Vietnamese lives do not revolve around that war despite American high school history textbooks often conflating the war with the country. Yet to move away and sever the Vietnamese American identity from the Vietnam War is to risk erasing the political and historical markers of our identity, where being “Vietnamese” becomes another flattened label in the United States’ multicultural project. So while I sympathize with those who want to move on from this pain, I also wholeheartedly agree with author Viet Thanh Nguyen, who states that our “history still demands an ongoing engagement with what that war mean(s), if we are not to concede its meaning to revisionist, nationalist agendas in the United States.” So we must continue to engage with this topic.

Vuong’s novel deftly straddles the tension between the necessity to talk about the war and the desire to move away. He produces something truly amazing where his refugees are more than the “good” refugees the United States continually perpetuates in its media for its own benefit. His refugees have lives after the war, and those lives are not always good.

Little Dog, the protagonist, is the first in his family to receive a college degree, positioning the United States as the land of opportunity and chances, but he is also a “yellow, queer” man that is discriminated against in this nation of refuge. As a child, Little Dog is bullied for not speaking English; he is pushed to the ground and humiliated until he is forced to say the name of his American tormentor. He learns “how dangerous a color can be. That a boy could be knocked off that shade and made to reckon his trespass. Even if color is nothing but what the light reveals, that nothing has laws, and a boy on a pink bike must learn, above all else, the law of gravity.”

Little Dog’s mother, Hong, is a manicurist at a salon like many Vietnamese women after the war thanks to the actress, Tippi Hedren, who volunteered with relief efforts. After some Vietnamese women complimented her nails, Hedren flew her personal manicurist to teach them how to become manicurists themselves and later helped them get licenses and employment. Hedren’s contribution, which might be construed as philanthropic, is also a form of the white savior attitude while simultaneously positioning the Asian/American body in service to the white body that needs to be grateful to white benevolence. Yes, Tippi Hedren is the godmother of the Vietnamese nail salon, but now the image of the Vietnamese manicurist haunts the Vietnamese American community. With that history in mind, Hong is not a submissive mindless body catering to the white figure in the few nail salon scenes, but rather a person with thoughts and agency. When a customer comes in bereft and in need of consoling after a recent loss, Hong takes care of her with genuine attention before realizing the customer is not talking about her daughter but rather her horse. The characters all laugh at this encounter, but this scene illustrates the emotional labor these women are expected to provide.

Hong’s character also juxtaposes the loving mother figure with a woman suffering from PTSD caused by a horrific war to illustrate the complicated feelings within the family. While Hong loves her son, she is also the same figure who enacts violence onto his body because she is struggling to cope in a new land that does not fully accept her. Vuong beautifully captures this sentiment with the line, “You’re a mother, Ma. You’re also a monster.”

Meanwhile, Little Dog’s grandmother, Lan, is more than the “Me so horny” Vietnamese prostitute made infamous by Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. Yes, she is a sex worker like other Vietnamese women who were forced into the occupation during the war, but she is also a single mother who has left a forced marriage trying to make ends meet during the war. She is later a grandmother who is trying to adapt to a new land as a refugee forcefully separated from her American GI husband by the husband’s mother and brother. As a refugee, she is positioned as a body in need of saving but is not deemed by the white family as a desirable body for their son/brother.

As Yen Le Espiritu, professor of ethnic studies at UC San Diego, argues in her book Body Counts, the Vietnamese refugee body is used to rehabilitate the negative United States image “from military aggressors into magnanimous rescuers.” These refugee bodies are simply seen as bodies that need to be saved and desperately fleeing from their home nation. But as Vuong shows with all his characters, the refugees are people with agency who also highlight the contradictions posed within the United States.

The gift of freedom, a term scholar Mimi Thi Nguyen coins in her book, The Gift of Freedom, dictates that the refugees must be grateful to the same nation that enacted atrocities, bombed their homeland, and created their refugee status. The ones who do survive the war and escape to the United States are thus seen as the “lucky ones” who have no problems. Yet us “lucky ones” still face discrimination and inequities that they cannot escape within this supposedly free nation. They still face pain and grief and trauma – all of which does not miraculously go away after the war has ended or after they are rescued from the communist threat. Because despite being given this gift of freedom, this freedom is an illusion. In the last part of the book, Vuong writes, “All freedom is relative—you know too well—and sometimes it’s no freedom at all, but simply the cage widening far away from you, the bars abstracted with distance but still there.”

Therefore, Vuong’s book is necessary for the subtle and brilliant ways in which it calls out these contradictions and complexities, for how it understands that we cannot move away from war literature yet despite our desire and sometimes need to. For these are the contradictions that affect how Vietnamese Americans are still seen today and how they are still located within a war context as bodies in need of saving.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is available from Bookshop, Book Soup, City Lights Bookstore, Open Books, Roscoe Books, and Skylight Books.

Justine Trinh is an English literature Ph.D. student at Washington State University. She graduated from the University of California, Irvine with B.A.s in Asian American studies and classical civilizations and a B.S. in mathematics. She then went on to earn her M.A. in Asian American studies, making her the first student to graduate from UCI Asian American Studies’ 4+1 B.A./M.A. program. Her research interests include Asian American literature, critical refugee studies, family and trauma, and forced departure and disownment.