By Essa Rasheed

Representation discourse, or the way we as a society talk about the representation of minority and marginalized groups in film, TV, literature, government, theater, business, and in our culture itself, has rapidly evolved in recent years. As “representation” has moved from being something you’d hear in media analysis circles to becoming a household term, there’s been a vile, but expected, reactionary response to it. Any time a minority is put center stage, there is an inevitable backlash of “oh, they’ve made it political.” I always hesitate to respond to such comments, because it needs to be said that they’re almost never made in good faith; the people who say things like that simply do not want to be reminded that minorities exist. Still, taking that type of talk at face value, I do feel an immediate impulse to say, “it’s not political, it’s just minorities existing.” But I also know that’s not entirely true—it’s much more complicated. If anything, the very existence of representation discourse has always been about one thing: there is something radical in the act of existing in a space you’ve been taught you’re not welcome. The everyday is political.

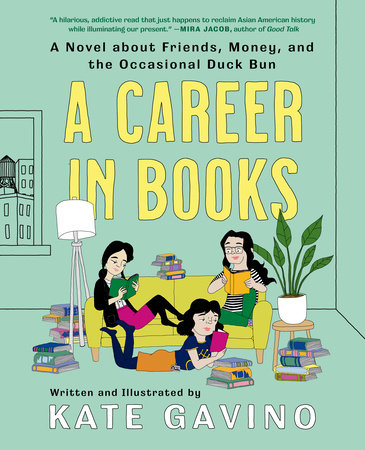

That thought was on my mind as I finished Kate Gavino’s graphic novel A Career in Books, which follows three Asian American best friends and roommates as they navigate their tumultuous post-graduation lives and begin their careers in publishing in New York City. The women find out their neighbor, a single elderly Vietnamese American writer named Veronica Vo, was once a prolific author, who, after winning a Booker Prize with her literary debut in the 1970’s, fell into obscurity. Though it isn’t a particularly challenging book, A Career in Books’ very presence feels significant. A group of friends living in New York City and trying to live their best lives is well-trodden ground, but it’s a rare treat to see that story told with Asian American main characters who frequent Asian American businesses and exist within an unashamedly and uncompromisingly Asian American community. I feel like this is the type of representation people have been waiting their whole lives to see – the sort of everyday representation that doesn’t feel exotified or commodified in any way.

Without a doubt, the book’s greatest strength is the friendship between the main characters, Silvia, Shirin, and Nina. Gavino perfectly captures the playfulness and joy of being young and living in a big city with your favorite people in the world. Central to that is a sophisticated chemistry to their friendship that genuinely feels as though it took years to develop. Little things like inside jokes, or a group chat with a funny name, or the way in which they’re able to effortlessly read each other’s emotions, all coalesce into a believable and vibrant bond.

For example, Shirin’s tumultuous relationship with her ex-girlfriend Priya becomes cemented as an inside joke as“The summer of Priya.” It’s used as a time marker in stories, with things being described as “before the summer of Priya” or “after the summer of Priya.” It’s dorky, but in a way that’s endearing and organic and feels like something a lot of people could relate to in the way their friend groups engage with the memories of someone’s bad exes. Even out of the context of their friendship, each of the women feels like a three-dimensional character, and her day to day struggles in an industry and a society that undervalues her feels real and relatable. At the best moments when the book hits its stride, you feel like you know these women and that you’re a member of their friend group, and the support and joy that radiates from their interactions feels infectious. I have a feeling a lot of the people that read this book will set a place for it in their collection of comfort reads. It’s certainly taken that place for me.

All of the main characters work for publishing companies of varying sizes, and the specifics of the publishing industry are portrayed with such knowledgeable frustration that I was certain Gavino was writing off of first-hand knowledge, and upon researching, found this to be the case. Gavino has mentioned how her own career in publishing fed into the novel in an interview with Nerdist. Gavino is able to portray a subtle demeaning quality inherent to office work in a way that I feel anyone that’s ever hated their job can relate to. The three women encounter nepotism, microaggressions, and a difficult work-life balance. The book leaves you with a sobering impression of the realities of not only the publishing industry but also of 21st century office labor at large.

However, the thing that sticks the most with me from this book is everything surrounding the aforementioned elderly retired writer and neighbor character Veronica Vo. The exploration of Veronica’s career is where much of the thematic sophistication and introspection of the book lies.

When people talk about representation, there is an unfortunate tendency to talk about art by minorities as though it is new, as if marginalized groups just now started having desires to be writers, artists, and musicians. The unfortunate reality of the situation is that the very systems of the financing, distribution, criticism, and preservation of media, systems steeped in the same prejudice as society that made them, have failed those artists. Even when authors are able to get published, they are not canonized in nearly the same way – there’s a reason why authors like Winnifred Eaton aren’t household names like F. Scott Fitzgerald. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Viet Thanh Nguyen has spoken on this, explaining how the whiteness of the industry gatekeeps who gets to be published and who gets canonized.

It is nothing less than a cultural tragedy how many great artists we have lost due to the bias of the systems by which we consume art, and Gavino seems conscious of this in her approach to the character of Veronica Vo. The manner in which the other characters approach the information that a great Asian American woman writer existed only to be pushed to obscurity in the very industry that they work in allows for a rich contemplation about literature, gender, race, representation, and American society.

Often, when an author writes about another author, there’s potential for some themes to exist at a metatextual level, and I would argue that’s also the case here as Gavino writes about Veronica Vo. As one of the main characters reads one of Veronica’s books, the narration reflects, “She could see why Veronica’s peers looked down on her work: she wrote about normal women whose biggest problems were workplace dilemmas or unhappy marriages. It was true: the books didn’t have dramatic conflicts or sudden twists, but Silvia found this comforting.” That sentiment perfectly illustrates this book’s approach to narrative, which is defined by a day-to-day meandering quality that’s charming and endearing. The narrative is episodic, with each chapter switching which character it follows throughout that point of their daily struggles. There isn’t the anxiety of an overarching threat; the stakes are small and intimate. It’s easy to dismiss these conflicts—struggles surrounding careers, friendships, relationships, and self fulfillment—as trivial. It is, after all, the stuff of media that’s so often called completely disposable, like Emily in Paris or Sex in the City. But Gavino embraces the humanity and universality of these topics while at the same time critiquing their trivialization.

My main criticism with the work is that, at times, it seems uncomfortable with being a graphic novel. It’s told in a pretty straightforward manner, without doing anything expressive or interesting with panel layouts or lettering, and I was never left thinking that this was a story that could only be told as a graphic novel. Additionally, The artwork feels overly simple in a way that can be distracting. The anatomy of the characters unproportionally warps from panel to panel in a way that is certainly an intentional aesthetic choice but comes across at times as compromised or unpolished. That isn’t to say that Gavino’s artwork is without merit – it’s just a style that I didn’t feel was adding much to the experience. Though I would generally recommend this as a book, there’s just a bunch of little things that make me hesitate recommending this to a graphic novel fan as a graphic novel.

Overall, A Career in Books is rich, comforting, intelligent and thoughtful, but never unapproachable or heavy-handed. Gavino creates likable, endearing characters who you want to see succeed while at the same time nestling reflections on labor, mental health, gender, race, and representation into resonant everyday struggles. In doing so, she presents the complexity of modern life with nuance and sophistication. It revels in the tremendous significance of the everyday and ordinary. There’s moments of reflection and growth that leave the book feeling like a beautiful coming-of-age story for people in their mid-twenties. It is a story that, like the Asian American women it follows, unashamedly and uncompromisingly occupies space in a way that is nothing less than bold and radical.

A Career in Books is available from Bookshop, Elliott Bay Book Company, Laguna Beach Books, The Last Bookstore, Talking Leaves Books, and Vroman’s Bookstore.

Essa Rasheed is a Pakistani American animator and illustrator from Corona, California. Rasheed graduated from the University of California, Irvine with B.A.s in English and film and media studies. He was previously a food writer for The Bloomsday Review.