By Audrey Fong

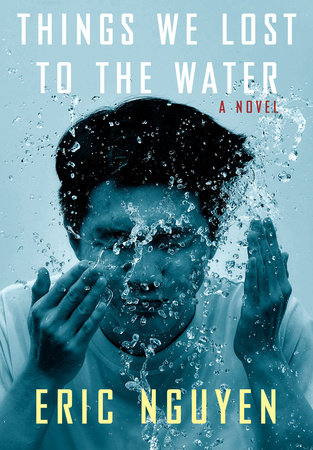

In Vietnamese, the word “nước” can mean two things simultaneously: water and country. This dual meaning plays heavily into the themes of Eric Nguyen’s debut novel, Things We Lost to the Water, a story about a Vietnamese refugee family grappling with the loss of a country and a father.

At the beginning, we meet Hương, a mother who has just arrived in New Orleans with her sons, five-year-old Tuấn and newborn Ben. During their escape from Vietnam, they lose their dad, Công, whose absence resonates throughout the novel. Not knowing what happened to him, Hương writes letters and records messages to send back to their old addresses in Vietnam, hoping these messages will reach him and that he will one day join them in the U.S.

Told from the perspectives of each of the major characters and spanning almost three decades, Things We Lost to the Water follows Hương, Tuấn, and Ben as they build new lives for themselves in the U.S. Initially, the plot revolves around Hương struggling to raise her increasingly defiant sons and how all three of them are attempting to make a home for themselves at Versailles, a group housing project for Vietnamese refugees in eastern New Orleans. The name of the community, Versailles, is both ironic, evoking the opulence of the French palace in contrast with the refugee’s relative poverty, and aspirational, a hope for a future for the Vietnamese American community that may one day be as comfortable as the court at Versailles. It also serves as a reminder of the role French colonization played in the Vietnam War and the subsequent refugee movements caused by the war.

As Hương supports the family, Tuấn and Ben explore their identities as Vietnamese Americans, start dating, and struggle in school. While Tuấn finds community in a Vietnamese American gang, Ben discovers his sexuality – as a teenager, practicing kissing with an older boy, and after college, falling in love with a man he meets when he moves to Paris.

From the family fleeing Vietnam by sea to Versailles residents tossing unwanted items into the bayou and the family trying to escape to higher grounds during a hurricane, the book is filled with water imagery. As seen by the family’s escape from Vietnam and the protagonists running through the rain as a hurricane forms, Nguyen plays with the idea of water and how it can symbolize, provoke, and be a means of escape. When Versailles residents toss unwanted objects into the bayou behind the community, the objects sink slowly until they are forgotten and lost in the brackish water, representing how unwanted memories and trauma can be pushed down into the back of people’s minds – not seen, but still there.

Additionally, what is interesting about the repeated water imagery is how water, and drowning by it, represents the intergenerational trauma that affects Hương, Tuấn, and Ben. In one chapter, Nguyen switches back and forth between Ben’s nightmares dealing with water and Hương and Tuấn struggling with the rainstorm signaling an approaching hurricane. Ben, now an adult and living in Paris, “closes his eyes. And again he sees water. He sees it everywhere.” In the dream, Ben sees his mother and brother screaming on a boat. He recognizes in the dream that he is still in his mother’s stomach and is watching a memory of a fight break out on board their ship that results in a boy being thrown overboard. Ben was not alive at the time of their escape from Vietnam; his mother was still pregnant with him. However, he is able to see part of their journey in this nightmare and therefore, better able to understand his mother’s and brother’s trauma that they live with every day ever since witnessing these acts of violence. From this memory, passed down through generations or by shared DNA, Ben is better able to connect his family’s journey across the ocean with the loss of a country and of a home.

Nguyen’s novel reminds me of how water, intergenerational trauma, and the loss of a country are wound together in Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do and Viet Thanh Nguyen’s “Black Eyed Women,” both stories that follow Vietnamese refugees. This connection’s prevalence in Vietnamese-American literature makes sense given the historical background. Millions of refugees from Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam fled their respective home countries by boat in the aftermath of the Vietnam War, leading them to be dubbed boat people. On any water vehicle available, these refugees crossed oceans to find safety at refugee camps spread across Asia in cities and countries like Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. Some were processed by U.S. armed forces in Guam and first entered the U.S. through naval bases like Camp Pendleton. Their flight by sea and processing at naval bases further strengthens the connection of loss of country with water.

Nguyen’s Things We Lost to the Water is a fast paced and interesting look at the Vietnamese American community in New Orleans. It reminds us of the connection between their presence in the U.S. and war, while also introducing readers to the idea of nước and the interconnectedness of water and country. It gives readers, who are used to narratives surrounding the Vietnam War written by non-Asian authors, a look at how the war impacted Asian people and their lives in the decades after the war concluded.

Things We Lost to the Water is available from Barnes & Noble and Penguin Random House.

Audrey Fong is a writer, interested in food, coming of age stories, and Asian American narratives. She earned her B.A. in English from UC Irvine and is currently pursuing an M.F.A. in creative writing from Chapman University. She is the co-founder and co-editor of Soapberry Review.