By Justine Trinh

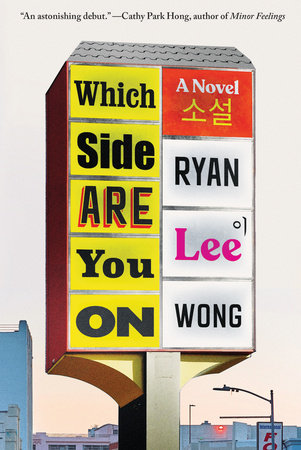

At its core, Ryan Lee Wong’s debut novel, Which Side Are You On, is a story about activism. The protagonist, Reed, wants to drop out of his prestigious Ivy League university to dedicate his life to the Black Lives Matter movement. The story pulls from both Wong’s own family roots in activism and presumably, his own research on 1970s Asian American movements conducted for his exhibitions, Serve the People at the Interference Archive and Roots at the Chinese American Museum. However, like Reed’s mother in the novel, Wong challenges us to rethink what activism is and what it can be as he attempts to parse out the nuances between Black-Asian interactions.

Set against the backdrop of Akai Gurley’s death at the hands of police officer Peter Liang, in 2014, Reed is part of the organizing efforts to hold Liang responsible. His form of activism is that of the traditional model of protests, marches, and “burn down the system” acts. Most of the time, Reed comes off as self-righteous and hardheaded, unable to comprehend nuances and choosing to see things as black and white, parroting what his activist friends at school say instead of forming his own opinions. His attitude reeks of you’re either with me or against me with no middle ground, as evidenced by his interactions with his high school friends at a Koreatown nightclub. Although Reed is right to call out the racist attitude towards an interracial couple, he ends up isolating himself from the community he is trying to reach and comes off as condescending. As his best friend, CJ, states in their argument, “In that case, you don’t want to be around my mom, my aunts and uncles, my grandparents, most of fucking K-Town.”

However, through conversations with his mother, who was once the leader of a Korean-Black coalition, Reed is forced to rethink some of the governing principles that guide his activist efforts. In one of his early conversations with his mother, she admits that she does not understand why Reed wants Liang to go to jail considering he did not previously call for white police officers to go to jail. She does not let this issue drop as she later points out Reed’s hypocrisy towards abolition: he both calls for Liang’s arrest while purporting to be an abolitionist. Reed is forced to confront what he (thinks he) knows with reality as he travels with his mother throughout his hometown of Los Angeles to understand what she puts forth as activism.

For me, Which Side Are You On was initially a slog to get through. I found Reed’s character so unlikeable and annoying. To be fair though, haven’t we all been like that at some point in our lives where our idealism comes off as moral superiority? It takes multiple life lessons and plenty of time to understand the intricate nuances of our world, and that there is so much gray in the middle ground that does not always match our personal ethics. At some points, the novel is very didactic, coming off as a “how to” manual rather than a work of fiction, but Wong crafts a story of realistic growth. The audience sees Reed gradually mature with every conversation and interaction, and Wong brings in many great points of discussion such as Asian American masculinity and Black-Asian relations. This book is very timely with recent events that have us all evaluating who we are and where we stand in a post-George Floyd world. To work in Wong’s title, his book has us questioning “which side are [we] on.”

Which Side Are You On is available from Bookshop, Eastwind Books, The Last Bookstore, Magers & Quinn Booksellers, The Poisoned Pen, and Powell’s City of Books.

Justine Trinh is an English literature Ph.D. student at Washington State University. She graduated from the University of California, Irvine with B.A.s in Asian American studies and classical civilizations and a B.S. in mathematics. She then went on to earn her M.A. in Asian American studies, making her the first student to graduate from UCI Asian American Studies’ 4+1 B.A./M.A. program. Her research interests include Asian American literature, critical refugee studies, family and trauma, and forced departure and disownment.