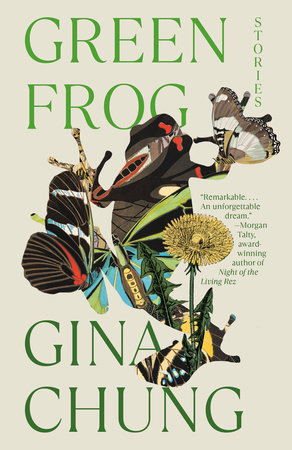

By Gina Chung

Gina Chung had me enthralled from the very first story in her wondrous and startling collection, Green Frog. “How to Eat Your Own Heart” instructs the proverbial you how to cut into your body, remove your heart, and then cook and eat it. Chung lists the steps—anatomically correct (I should know, I used to practice as a pediatrician) and frankly riveting—in a detached yet intimate manner. The fact that she ends this essay with aching tenderness is, to use a food cliché, icing on the cake. And I knew I was in the hands of a master storyteller.

I shouldn’t have been surprised. I loved her first book, Sea Change, a novel about a young Korean American woman and her relationship to a giant Pacific octopus named Dolores. A coming-of-age story, her novel had me laughing and crying, and sometimes, both at the same time.

In “Green Frog,” the titular story in her collection, Chung draws inspiration from a Korean folktale, and she also dips into the same source well with “Human Hearts,” which inhabits the point of view of a fox demon with nine tails that Koreans call a gumiho. Chung transforms allegories for children into heartbreaking human dilemmas. The green frog and the gumiho must both learn to make their own ways in the world. Fantastical elements in “Honey and Sun,” a story about twin girls and their talking dolls, transform into strangely ordinary and yet perfectly tragic facets of life. By the way, the image of a doll wringing her cloth hands is superbly funny and still inspires a smile whenever I think about those young girls, their dolls, and the butterflies that pervade their world.

In “Mantis,” a praying mantis “lives in a small but well-furnished and moderately priced studio apartment in an oak tree overlooking a baseball field in the park.” This first line made me laugh out loud. Who doesn’t want a beautiful rent-controlled place to live? The anthropomorphizing of an insect and her desires in Chung’s capable hands feels natural, believable, and funny. Within just a few pages, I traveled with a praying mantis in her emotional arc of dating and falling in love, as well as the consequences of those actions.

And then there are the human stories in this collection—so affecting that I found myself crying after reading one. In “Attachment Processes,” a mother grieves the loss of her child and desperately wants to mend their relationship. Her grief is palpable. Honestly, I expected a completely different ending to the story and was surprised and delighted when Chung pulled off what feels like the only ending that makes sense—equal parts sorrow and joy. A balancing act of enormous skill yet effortless grace. “Names for Fireflies” will never allow me to look at fireflies in the same way. That metaphor is so appropriate for this story about two girls on the precipice of adulthood, connected in a manner irrevocable and searing. Likewise, I’m still haunted by “You’ll Never Know How Much I Loved You,” a story about grandmothers and granddaughters, husbands and wives. The kinds of love that endure and those that combust and what we’re left with in the aftermath. In “The Love Song of the Mexican Free-Tailed Bat,” Chung has a line so true, so resonant I stopped breathing: “At times, you are not sure where your anger ends and your father’s begins.” In this last short story, a daughter must come to terms with the death of her father, and her hard-won insight at the end (I won’t spoil it here) allowed me to see my own father’s death just a little bit clearer. Chung’s use of the second person point of view adds an authentic poignancy to the story, instead of detracting from it.

Throughout the collection, Chung deftly switches perspectives from first person, second person, third person, and even the collective “we,” uncannily choosing the needed point of view for each story. A narrator’s POV is inseparable and integral to a story and if I didn’t admire her so much, I’d be broilingly jealous of Chung’s fluent mastery of point of view. There are no easy answers or easy endings in Chung’s stories. Because how can you reduce life’s complications to platitudes? Chung lays bare the difficulty in living whether you’re a frog or a praying mantis or a human, yet she unfolds hope like jewels with her use of language, metaphor, and imagery.

Humans are built for narrative. We like stories that make us wonder and think and laugh. But we love stories that make us feel, remind us of the human condition—what we mean to each other, to ourselves, to the world. What a tour de force Gina Chung has achieved in Green Frog. I savored every story in this collection—not a weak link in the bunch. Green Frog shimmers with the beauty of Chung’s words and the beauty and comedy and grief of being alive.

Green Frog is available from Bookshop, City Lit Books, Loyalty Bookstores, Skylight Books, Trident Booksellers & Cafe, and Women & Children First.

Helena Rho is a four-time Pushcart Prize nominated writer and the author of American Seoul: A Memoir. A former assistant professor of pediatrics, she has practiced and taught at top ten children’s hospitals: Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Johns Hopkins Hospital, and Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. She earned her MFA in creative nonfiction from the University of Pittsburgh and is a devoted fan of K-Dramas, Korean green tea, and the haenyeo of Jeju Island. Stone Angels, her debut novel, is forthcoming from Grand Central Publishing in March 2025.