By Thu Anh Nguyen

It’s too easy to read autobiographically into Ocean Vuong’s writing even though he cautions you against it. In his first collection of poetry Night Sky with Exit Wounds and even more so in his first novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, he invites you into his love and grief so personally that you can’t help but think that he’s revealing the facts of himself to you. While Vuong insists that his family still possess their own lives outside his text, the intimacy he creates makes you feel like you know them.

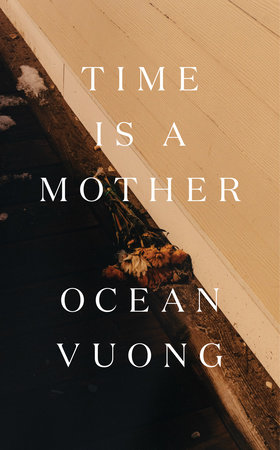

With Vuong’s third publication, a collection of poetry entitled Time Is A Mother, the writing is no less personal, but I experience an even more powerful urge than to assume his writing is autobiographical: I cannot read these poems without reading myself into them.

I am Vietnamese. I am a poet. My father died three years ago. I could list so many points of resonance between my life and Vuong’s life. I’m not the only one who feels this spark of recognition: when moderating a book talk with Vuong for Powell’s City of Books, the writer Jia Tolentino spoke of a kinship she felt with Vuong in part because they were born weeks apart, but mostly because of the magic of his writing.

How could I read a poem as audacious as “Amazon History of a Former Nail Salon Worker” and not think of my own aunts and uncles who work in nail salons, who have also had to order cuticle oil and acrylic nail tips in bulk like the anonymous worker of the poem? What seems at first glance like just a supply list with no commentary becomes a stark accounting of illness and a reduced life as the orders become more about medical supplies such as a “Lumbar Support Back Brace” and “Chemo-Glam cotton head scarf.” All of a sudden I am transported to my grandmother’s cancer, how she needed so little in the end. It makes sense to me that the last thing ordered on Amazon in Vuong’s poem is only 1 pair of “Wool socks, grey.” Vuong’s specificity doesn’t just make his writing universal; it makes it personal to me.

Vuong has said in past interviews that death is the only thing we have in common, that we all lose our parents, and are headed to the same place we go. We are united in grief.

But grief is not all the collection is. Many reviewers of Time Is A Mother have called the collection an elegy for his mother who passed away from cancer, and although it does lament the death of Vuong’s mother, there is so much joy and humor in the book that it’s like no elegy I recognize.

Vuong is a master of invention, and has called himself a “junkyard artist.” He’s taken the elegy and turned it into a sonata, given it a rhythm and rhyme that dances off the page. He plays with language in poems like “Beautiful Short Loser” that make you reconsider what it means to be a winner or a loser. This is something he’s learned as an immigrant, and it’s something I know deeply.

Vuong and I were both born in Saigon, and emigrated to the United States, the place that was pivotal to the loss of our birthplace. And somehow, we both fell in love with the language of our new home, or maybe it was that we fell in love with language in general.

Like Vuong, I spoke Vietnamese before I learned English, and like him, I have a hard time with verb tenses. He explained this elegantly in an interview with The Creative Independent where he talked about how the Vietnamese language doesn’t have past participles, so everything is spoken in the present.

Perhaps that trouble with verb tense is also related to our reckoning with language. How do you translate a culture? How do you translate a language so much older than the one you speak most regularly? What if the language you speak most regularly is violent, and is not the way you want to represent yourself? In his poem “Old Glory,” Vuong writes in a tight, 14-line poem many of the awful phrases we use in English to praise each other: “Knock ‘em dead, big guy. Go in there/guns blazing, buddy. You crushed…” Whenever I see a 14-line poem, I can’t help but think of a sonnet, but if this poem is a sonnet, it’s no traditional love poem. This love is brutal the way that brutality is embedded into the English language’s metaphors.

Vuong doesn’t stop at recognizing that brutality; he transforms it. When Vuong talks about reclaiming language to center wonder and joy, he says that it’s because “what was there was never friendly to [him]. It is the story of being queer, of being Asian American.”

What I love about Vuong’s writing, especially in his most recent poems, is the way he reclaims language because, after all, “no regime can possess language,” and so “the writing is the reclaiming.” This isn’t just a building on top of an old structure, or a simple layer of paint. Vuong knows that brokenness has to be part of the reclamation, that we can’t just erase the trauma that resulted in brokenness.

What Vuong reclaims in Time Is A Mother is his childhood, and mine. When speaking of his mother, Vuong says that what happens after you lose a parent, no matter how old you are, is that you suddenly become a child again. As children once more, it’s easier to respond with joy to the world even while we are experiencing terrible grief. It’s my inner child that reads “The Last Dinosaur” and laughs at lines like “…my ass was once a small-town / wonder,” and aches at the ending truth that “I was made to die but I’m here to stay.”

Vuong explains that his writing contains an “optimism that goes hand in hand with disobedience.” There is the disobedience of the writer who writes an elegy so full of dancing, music, sex, and life, and there is the disobedience of the survivor, which Vuong and I both are. We were raised by survivors of the American War in Vietnam; they survived because of their sense of wonder and awe that persisted in spite of that war.

We were raised by survivors who had to remake worlds for us. There are so many poems in Time Is A Mother that are about creation, biblical and metaphorical, including at the very end of the book. In the final poem “Woodworking at the End of the World,” there is a dead mother and a child. There are flashes of images like the child’s eyes that remind the speaker of the poem of the buttons from the coat used to cover his mother’s face at the end. The speaker looks for a gun, but he thinks he “must’ve dropped it while burying [his] language / farther up the road.” The violence comes and goes. Life is there with death. Lastly, the speaker remembers his life “the way an ax handle, mid-swing, remembers the tree,” and proclaims “& I was free.” That ending reads to me exactly like the whole collection: rooted in love and memories while shimmering with the energy of forward motion.

In his talk with Tolentino, Vuong said about his work with the English language: “I’m going to use these tools that you threw away.” In Time Is A Mother, Vuong is a craftsman who uses language to remake the world, and it is a place that I not only recognize because so much of it is a mirror of my own life, but it is where I want to stay for as long as he’ll have me because it teaches me to love myself, and where I’ve come from.

Time is a Mother is available from Alexander Book Company, Barnes & Noble, City Lights Bookstore, Eastwind Books, The Last Bookstore, Linden Tree Books, and Powell’s City of Books.

Thu Anh Nguyen is a poet whose poetry has been featured in the Southern Humanities Review, Cider Press Review, NPR’s “Social Distance” poem for the community, The Crab Orchard Review, The Salt River Review, 3Elements, Connections, and RapGenius. She also writes about equity, justice, and community through literacy. Her essays on the importance of reading diverse literature have been featured in Literacy Today.